Click on image for full size

Courtesy of Zina Deretsky, National Science Foundation

Fish Adapting to a Changing World

News story originally written on October 8, 2008

The stickleback fish, Gasterosteus aculeatus, is one of the most thoroughly studied organisms in the wild, and has been a particularly useful model for understanding variation in physiology, behavior, life history and morphology caused by different ecological situations in the wild.

On biological levels from molecular and genetic to developmental and morphological, and finally ending with the population level, it has proven far more complex than even imagined.

Studies of stickleback have provided us with a much better understanding of how organisms cope with new environmental conditions, first through acclimation over an individual's lifespan, and subsequently through adaptation of population via changes in gene form (allele) frequencies.

Given the rapidly changing global environment, this research not only provides insight into evolutionary processes, but is of practical importance in understanding how organisms will adapt to a changing world.

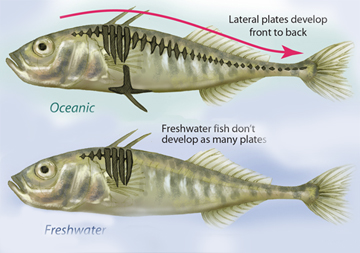

There are two forms of the stickleback: the oceanic and the freshwater type. The oceanic form lives in the ocean and comes into shallow estuarine or freshwater rivers and streams to breed, and has repeatedly given rise to a freshwater form that lives its entire life isolated in freshwater habitats.

Oceanic stickleback are protected by a complete set of bony lateral plates along the sides and dorsal and pelvic spines on the top and bottom of the fish. These structures help the fish survive attacks by birds and other fish-eating predators. The lateral plates develop first at the front of the fish, near the spines, and then are gradually added towards the tail until the entire side of the stickleback is covered.

Freshwater stickleback almost always evolve the loss of lateral plates, and sometimes the spines, as shown in the figure. This evolutionary change can occur very rapidly, sometimes in only dozens of years. An explanation for the loss of the bony plates is that energy is shunted away from bone formation and toward growth and reproduction instead, especially since the freshwater environment is stressful to the fish. In contrast to the ocean, freshwater lakes (especially in the far north) become iced over, limiting the prey items available to stickleback throughout most of the winter.

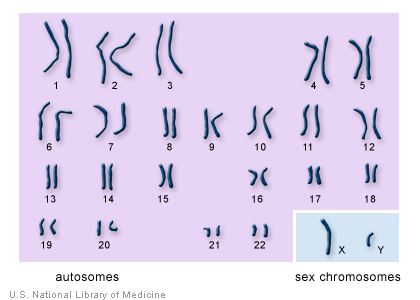

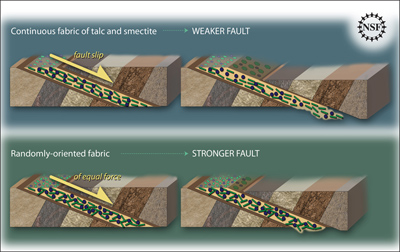

Coding for the lateral plates was initially determined to have a relatively simple genetic basis with one gene identified as a major contributor, Ectodysplasin-A (Eda). However subsequent mapping showed that in addition to the region of the genome surrounding Eda, two additional blocks of the same chromosome were also tightly linked to each other and the lateral plate trait. Genetic mapping work on Alaskan stickleback was conducted by William Cresko at the University of Oregon and supported by the National Science Foundation.

Fish develop full lateral plates if they have at least one copy of the Eda complete version of the gene (heterozygous or homozygous for the Eda complete allele). The fish lack the full complement of plates if they are homozygous for the recessive gene--Eda low. From the laboratory mapping results, and the rapid loss of plates observed in nature, biologists hypothesized that selection would always be for the Eda low allele in freshwater.

An experimental test by Barrett et al. has shown surprisingly unexpected results in fitness of the fish. The fish's lifespan is approximately a year. Over the course of a year, researchers sampled a controlled population of stickleback. They found that early in life, fish with Eda low were not as successful.

However, midway through their life, the tables turned and the fish with a copy of Eda low were more successful at surviving. In retrospect, these data might not be so surprising given the results from Cresko on the additional linkage blocks. Selection is likely directly on the Eda alleles when the fish is older, but may be on the other linked genomic blocks when the fish is younger, leading to a correlated change in Eda alleles. A challenge now is to determine what these other genes are, and how they might affect traits and fitness.

Text above is courtesy of the National Science Foundation