Click on image for full size

Courtesy of the Ocean Remote Sensing Group, Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory

The Swirling Water of Ocean Eddies

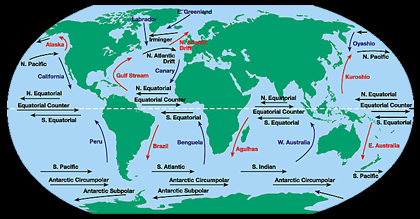

Surface ocean currents move in predictable directions over time. However, on a smaller scale, the water in currents moves in complex and variable ways. And those complexities can cause some water to spin away from a current, creating an eddy.

The swirling water of an eddy can be more than 100 km (60 miles) in diameter. The center of some eddies is cool while the center of others is warm. Warm water eddies are usually nutrient poor and marine life is sparse in them. Cold water eddies are usually nutrient rich and full of life.

Eddies form when a bend in a surface ocean current elongates over time, making a loop. The loop separates from the main current to form the eddy. The Coriolis effect causes similar eddies to rotate in opposite directions in the different hemispheres so that in the north, cold water eddies rotate counterclockwise and warm water eddies rotate clockwise, while in the south, cold water eddies rotate clockwise and warm water eddies rotate counterclockwise. There is evidence that the topography of the ocean floor can help eddies to form too. Once an eddy forms, the swirling waters last for at least a few months.

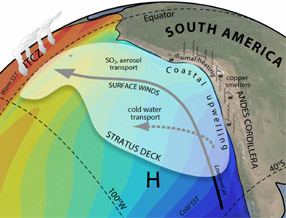

The satellite image at the left of sea surface temperatures (SST) shows two large circular features above the Gulf Stream current in the Atlantic near the northeast coast of the United States. These are eddies. In this image, surface water is colored depending on its temperature with blues and purples for the coldest water and orange and yellow for warmer water. The orange color of these eddies indicates that they are warm water eddies. This area of the ocean – the Gulf Stream - tends to have some of the largest and most well defined eddies in the world.