Click on image for full size

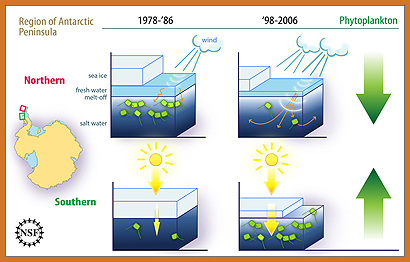

Courtesy of Zina Deretsky / NSF

Warmer Temperatures are Changing Antarctic Phytoplankton

News story originally written on March 16, 2009

Over the past 50 years, winter temperatures on the Antarctic Peninsula have risen five times faster than the global average. Warmer temperatures mean that there is now less sea ice in the nearby Southern Ocean. This is bad news for Antarctic marine life that depend on sea ice, like Adelie penguins. Their numbers have decreased in the northern part of the Peninsula while penguins that avoid ice, such as Gentoo and Chinstrap penguins, are moving into the area.

The changing climate isn’t just affecting the penguins at the top of the food chain. New research shows that it’s also affecting tiny microscopic creatures at the bottom of the food chain. Diatoms, a type of phytoplankton, are the start of the Antarctic food web. These single-celled creatures float in ocean water and, through photosynthesis, get their energy from the Sun.

By studying satellite data on ocean color, temperature, sea ice and winds, scientists have found that phytoplankton are changing as the area’s sea ice and winds change because of global warming.

The phytoplankton in the northern and southern areas of the Antarctic Peninsula is not changing in the same way. That surprised the scientists.

In the north, there is less sea ice and more wind. This combination causes the sea water to mix more than it used to. The mixing decreases the amount of sunlight that gets through the water. With less sunlight, phytoplankton are doing less photosynthesis.

In the south, sea ice used to cover most of the seawater for most of the year. Now, there is less sea ice, which exposes seawater to sunlight. More sunlight leads to more photosynthesis and more phytoplankton. There is also less wind in the south, so the layer of the seawater that is mixed is smaller than in the north. More sunlight gets through the water allowing the phytoplankton to do more photosynthesis.