Click on image for full size

Courtesy of the Center for Snow and Avalanche Studies

Desert Dust Alters Ecology of Colorado Alpine Meadows

News story originally written on June 29, 2009

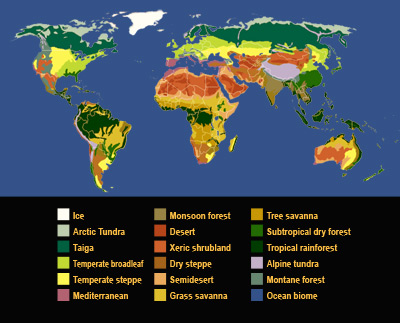

Dust blown into the San Juan Mountains of Colorado is causing snow to melt faster in the springtime. Scientists have found that this is changing how alpine plants that live on the high mountain tundra react to changing seasons, indicating that global warming could have a big impact on plant growth.

The dust is from the desert areas in the southwest United States. Today, five times more dust blows into the mountains than 150 years ago. More human activity in the desert is creating more dust. Also, climate change is causing the desert to get warmer and drier, which will likely cause even more dust to blanket mountain snow in the future.

"It's striking how different the landscape looks as result of this desert-and-mountain interaction," said scientist Chris Landry, who contributed to the study. The snow that remains in the spring is so covered with desert dust that it looks like soil. Dark colored dust reflects less sunlight than white snow. This retains more heat, causing snow to melt faster.

When snow on mountaintops melts slowly through the warmer months of the year, there is a steady supply of water for the ecosystem and for cities, towns, and farms. However, when dust causes snow to melt quickly in the spring, there is less water for the ecosystem and for humans during summer and fall.

To study the impact of dust on snow and tundra plants, the scientists simulated dust effects on snowmelt in areas of the San Juan Mountains. They measured how much dust sped up snowmelt, and how the life cycles of alpine plants were changed.

The timing of snowmelt signals to mountain plants that it's time to start growing and flowering. Early snowmelt caused by dust could change this, which could affect the whole ecosystem. For example, many species of plants could flower at the same time, increasing competition for water and nutrients.

"With increasing dust deposition from drying and warming in the deserts," said scientist Heidi Steltzer, who led the study, "the composition of alpine meadows could change as some species increase in abundance, while others are lost, possibly forever."