Click on image for full size

Courtesy of U.S. Geological Survey

As World Warms, Water Levels Dropping in Major Rivers

News story originally written on April 21, 2009

Rivers in some of the world's most populous regions are losing water, according to a comprehensive study of global stream flows.

The research, led by scientists at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder, Colo., suggests that the reduced flows in many cases are associated with climate change, and could potentially threaten future supplies of food and water.

The results will be published May 15 in the American Meteorological Society's Journal of Climate. The research was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF), NCAR's sponsor.

"The distribution of the world's fresh water, already an important topic," says Cliff Jacobs of NSF's Division of Atmospheric Sciences, "will occupy front and center stage for years to come in developing adaptation strategies to a changing climate."

The scientists, who examined stream flows from 1948 to 2004, found significant changes in about one-third of the world's largest rivers. Of those, rivers with decreased flow outnumbered those with increased flow by a ratio of about 2.5 to 1.

Several of the rivers channeling less water serve large populations, including the Yellow River in northern China, the Ganges in India, the Niger in West Africa and the Colorado in the southwestern United States.

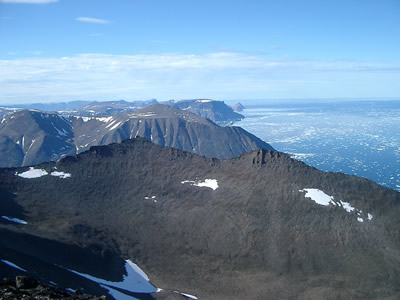

In contrast, the scientists reported greater stream flows over sparsely populated areas near the Arctic Ocean, where snow and ice are rapidly melting.

"Reduced runoff is increasing the pressure on freshwater resources in much of the world, especially with more demand for water as population increases," says NCAR scientist Aiguo Dai, the lead author of the journal paper. "Freshwater being a vital resource, the downward trends are a great concern."

Many factors may affect river discharge, including dams and the diversion of water for agriculture and industry.

The researchers found, however, that the reduced flows in many cases appear to be related to global climate change, which is altering precipitation patterns and increasing the rate of evaporation.

The results are consistent with previous research by Dai and others showing widespread drying and increased drought over many land areas.

The study raises wider ecological and climate concerns.

Discharge from the world's great rivers results in deposits of dissolved nutrients and minerals into the oceans. The freshwater flow also affects global ocean circulation patterns, which are driven by changes in salinity and temperature, and which play a vital role in regulating the world's climate.

Although the recent changes in freshwater discharge are relatively small and may only have impacts around major river mouths, Dai said the freshwater balance in the global oceans and over land needs to be monitored for long-term changes.

Scientists have been uncertain about the impacts of global warming on the world's major rivers. Studies with computer models show that many of the rivers outside the Arctic could lose water because of decreased precipitation in the mid- and lower latitudes, and an increase in evaporation caused by higher temperatures.

Earlier, less comprehensive analyses of major rivers had indicated, however, that global stream flow was increasing.

Dai and his co-authors analyzed the flows of 925 of the planet's largest rivers, combining actual measurements with computer-based stream flow models to fill in data gaps.

The rivers in the study drain water from every major landmass except Antarctica and Greenland and account for 73 percent of the world's total stream flow.

Overall, the study found that, from 1948 to 2004, annual freshwater discharge into the Pacific Ocean fell by about 6 percent, or 526 cubic kilometers--approximately the same volume of water that flows out of the Mississippi River each year.

The annual flow into the Indian Ocean dropped by about 3 percent, or 140 cubic kilometers. In contrast, annual river discharge into the Arctic Ocean rose about 10 percent, or 460 cubic kilometers.

In the United States, the Columbia River's flow declined by about 14 percent during the 1948-2004 study period, largely because of reduced precipitation and higher water usage in the West.

The Mississippi River, however, has increased by 22 percent over the same period because of greater precipitation across the Midwest since 1948.

Some rivers, such as the Brahmaputra in South Asia and the Yangtze in China, have shown stable or increasing flows. But they could lose volume in future decades with the gradual disappearance of the Himalayan glaciers feeding them, the scientists say.

"As climate change inevitably continues in coming decades, we are likely to see greater impacts on many rivers and the water resources that society has come to rely on," says NCAR scientist Kevin Trenberth, a co-author of the paper.

Text above is courtesy of the National Science Foundation