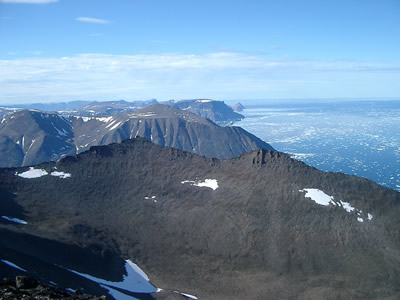

Click on image for full size

Courtesy of Anne Pharamond

Reef Health Depends on Algae Chomping Fish

News story originally written on October 31, 2007

The health of coral reef ecosystems is endangered by many different forces – warming seas, carbon dioxide, diseases, fishing, and pollution to name a few. Can reefs recover once they become unhealthy? According to the results of a recent study, Caribbean coral reefs can become permanently unhealthy if algae-eating animals, such as parrotfish and urchins, dwindle. The study's results suggest that for Caribbean coral reefs to survive, especially given the predicted impact of climate change, parrotfish need to be protected.

A healthy coral reef is teeming with life and bustles like a colorful, diverse city. Much of a healthy coral reef is made by coral animals, which live in colonies that build the rocky structures that give a reef its shape. Large numbers of other species also call coral reefs home. Large eels and rays, tiny snails and shrimp, and numerous fish are all reef inhabitants. Yet, an increasing number of reefs, especially in the Caribbean, are becoming unhealthy and overrun by algae. Algae are a natural part of the reef ecosystem too, but the stress of pollution or fishing can cause algae to overgrow a reef, taking over areas where corals once lived.

Many Caribbean reefs became covered with algae when a sea urchin called Diadema antillarum nearly went extinct in the 1980s. Urchins, spiny relatives of sea stars and sand dollars, may be relatively simple animals without heads or even a backbone, yet they play a big role in a reef. Diadema antillarum urchins eat algae. They trundle slowly across the reef scraping algae from the surface and creating space for corals to grow. This helps keep the reef healthy. Today the urchins are recovering in some parts of the Caribbean, but in other areas, they have not returned.

Reefs without the urchins now rely on other creatures that eat algae, namely parrotfish, to keep algae from growing unchecked. Parrotfish have a special hard plate in their mouth that enables them to bite at algae-covered reef rocks, eating the algae along with a bit of rock from the spot where the algae attached. All that munching by the parrotfish on a reef makes an audible crunching sound underwater. However, there are less parrotfish on reefs today. Caribbean parrotfish are caught in fish traps and many of them end up on dinner plates. Without the urchins and parrotfish that keep algae populations in check, reefs can become covered with algae and unhealthy.

A team of scientists wanted to test whether Caribbean reefs that are overgrown with algae could return to good health if the causes of the problem, such as fishing or pollution, were fixed. The scientists created a computer model that simulates the conditions of Caribbean reefs. They looked at what happened to the health of the model reef when factors, such as the number of parrotfish, were changed. The research team discovered that without enough parrotfish munching algae from the reef, more of the reef surface becomes covered with algae and corals become less healthy. They found that in this unhealthy state a reef is less likely to recover from a disturbance like a hurricane. Coral reefs can become permanently unhealthy.

“The future of some Caribbean reefs is in the balance and if we carry on the way we are then reefs will change forever,” said Peter Mumby of the University of Exeter, one of the researchers who developed the model. “The good news is that we can take practical steps to protect parrotfish and help reef regeneration.”