Click on image for full size

Image courtesy of the U.S. Natl. Park Service, photograph by Al Mebane.

Extremophiles

Some environments are inhospitable to most "normal" living creatures. However, these extreme environments are not necessarily lifeless. Certain types of organisms, known collectively as "extremophiles", have adapted to survive or even thrive in various types of extreme environments. Philia is the Greek word for "love", so extremophiles are organisms that "love" extreme environments.

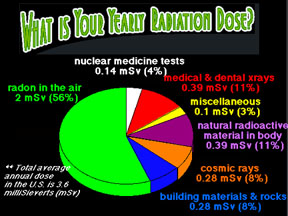

Most, though not all, extremophiles are microbes. In the last few decades, scientists have discovered many types of organisms that can survive in difficult environments that were previously thought sterile. Extremophiles have been found in very hot and in very cold environments; in exceptionally dry deserts; in environments that are very acidic or alkaline or doused in other harsh chemicals; and even in places exposed to high levels of radiation. These discoveries have generated lots of interest in life in extreme environments in recent years.

Early in our planet's history, most environments on Earth were extreme by modern standards. Likewise, environments on alien worlds within our Solar System and beyond are often marginally habitable if at all. The study of extremophiles may shed light on the origins and early evolution of life on Earth. Likewise, our knowledge of extremophiles may help us gage the likelihood of life arising in various extreme environments on planets and moons in our Solar System and beyond. The relatively new science of astrobiology is concerned with the study of such organisms.

Scientists have special names for extremophiles that thrive in specific types of challenging environments. Thermophiles live in hot environments (60-80° C, or 140-176° F); hyperthermophiles live in really hot places (80-122° C, or 176-252° F). Acidophiles like acidic conditions, with a pH of 3 or lower. Halophiles live in salty environments, cryophiles (or psychrophiles) like the cold, and xerophiles thrive in very dry deserts. Some organisms live in environments that are extreme in multiple ways; certain microbes that dwell in acidic hot springs are thus both thermophiles and acidophiles.

Though not technically extremophiles, numerous larger organisms are also adapted to survive in environments that would be lethal to most creatures. Camels are famously capable of going for long periods without water in the deserts in which they live. Emperor penguins somehow manage to make it through bitter Antarctic winters. Extreme plants, such as the many species of cactus, cope with the heat and dryness of desert environments as well. Bizarre tube worms grow in the superheated and chemically exotic niches around deep sea hydrothermal vents.