Click on image for full size

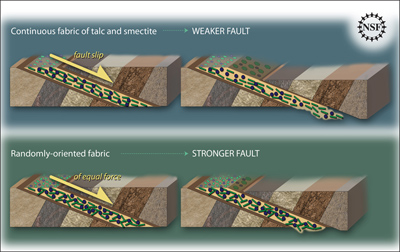

Courtesy of Kara Culligan and Eunji Chung, Harvard University; Lina Garcia, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Picture This: Explaining Science Through Drawings

News story originally written on April 28, 2008

If a picture is worth a thousand words, creating one can have as much value to the illustrator as to the intended audience. This is the case with "Picturing to Learn," a project in which college students create pencil drawings to explain scientific concepts to a typical high school student. The National Science Foundation (NSF), Division of Undergraduate Education, provides support for this effort.

What sets this project apart is its emphasis on inviting students to draw in order to explain scientific concepts to others. The act of creating pencil drawings calls into play a different kind of thought process that forces students to break down larger concepts into their constitutive pieces. This helps clarify the underlying science--from Brownian motion (the movement of particles suspended in a liquid or gas and the impact of raising the temperature of the liquid), to chemical bonding, to the quantum behavior of a particle in a box. In the same assignment, students are asked to evaluate their own drawings, which helps them identify and appreciate critical components.

"Visually explaining concepts can be a powerful learning tool," says Felice Frankel, principal investigator at Harvard University. "The other important part of this is that the teacher immediately identifies student misconceptions."

The project brings together five institutions: Harvard, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Duke University, Roxbury Community College and the School of Visual Arts in New York City. The students involved are undergraduates studying physics, chemistry and biology.

Each drawing assignment asks students to explain a science concept or process. For example, in addressing the question of how to identify which of two compounds has the higher boiling point, students are encouraged to be creative and to consider a variety of formats, including cartoons and stick figures. Students are also told, "In your drawing, strive for clarity in visually representing the concepts of bond type and strength."

Many of the drawings bring scientific concepts to life in interesting and unexpected ways. They also bring any misconceptions immediately to light so that professors can address them with students.

"I've been surprised and very pleased about the enthusiasm and excitement we've seen in some very renowned science professors," says Rebecca Rosenberg, the project manager and a former secondary school science teacher. "They could have pooh-poohed this idea, but instead, they're seeing how it helps inform their teaching."

Four Harvard physics majors will take their work to the next level on April 12, when they travel to New York City for a workshop with design students at the School of Visual Arts (SVA). The idea is to engage design students in conversation with science students so that each can learn from the other. In a previous workshop which involved students from SVA and MIT, the participants created an anthropomorphic metaphor, where "little guys" representing particles interacted with each other. As the students drew out the metaphor, they ultimately realized that this model wouldn't work. They scrapped it and started over, in the process developing a better understanding of both the concept and how to communicate it to others.

An eventual goal of the project is to expand it to students in middle school, high school and graduate school. In parallel, this approach is of growing interest to educators.

"This project promotes widespread adoption of these methods through workshops and publications," says Hal Richtol, NSF program manager. "Clearly it offers a useful teaching tool to anyone teaching science at any level."

The students' work, and a description of the project, is accessible at http://www.picturingtolearn.org/.

-NSF-